Tuhinga / Essays

Tai Moana Tai Tangata

View projectJoin the virtual tourGet the catalogue

Tai Moana Tai Tangata, a solo exhibition by Brett Graham, was held at:

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, New Zealand (December 2020 to May 2021)

City Gallery Wellington, New Zealand (August to October 2021)

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū (November 2022 to February 2023)

Displaying new work by Brett Graham, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery's 2019 Artist in Residence, Tai Moana Tai Tangata revisits key events of New Zealand history as witnessed by Māori who suffered the most severe penalties of the colonial process.

Engaging the architecture of warfare on the colonial frontier and the language of war memorials in times of peace, Tai Moana Tai Tangata commemorates historic relationships and political pacts between Tainui and Taranaki iwi in the face of new challenges wrought by European settlement.

Curator: Anna-Marie White (Te Ātiawa)

Catalogue: The accompanying catalogue, led by White and designed by Neil Pardington (Ngai Tahi, Ngāti Mamoe, Ngāti Waewae), contextualises this new body of work in relation to Brett Graham's practice, to produce the most comprehensive resource on this artist, along with commissioned responses from Darcy Nicholas (Te Ātiawa) and Dr Nancy Mithlo (Chiricahua Apache).

Events (Govett-Brewster Art Gallery): Virtual tour and A Taranaki Tribal Perspective (speaker series on the themes of Tai Moana Tai Tangata, bringing a Taranaki lens to continue the exhibition's narrative)

Articles:

Memories carved in relief (Art News New Zealand) – Govett-Brewster Assistant Curator Hanahiva Rose writes about the histories, prophecies and revisitations in the exhibition

Confronting New Plymouth exhibition shows colonisation through eyes of tangata whenua (Stuff New Zealand)

The past needs new authors (The Pantograph Punch)

Christchurch and the New Zealand Wars (Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū's Bulletin B.210)

On this page:

Review by Albert L Refiti

Essay by Peter Brunt

Review by Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua

Review

Author: Albert L Refiti

In a recent discussion that Brett Graham and Dame Anne Salmond had about the Māori notion of space-time or wā (30 March 2021 at the TeWānaga o Waipapa, University of Auckland), they concluded that wā is to be understood as an interlinked spiral of time and space, a dancing vortex that collapses past, present and future. We can see and experience wā only from a privileged position composed of moments organised around rituals and ceremonies. For architecture, it is how rituals are given their proper shape and form that creates a temporal place from which wā can unfold. Architecture in this context can only be an apparatus that congeal materials in the shape of rituals.

Brett Graham's Tai Moana Tai Tangata exhibition at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth expresses this effusively. Opened in December 2020 until May 2021, the show was two years in the making for Graham. To experience this work on a stepping 4-level vertical space is to be enveloped by a place that is saturated with narratives of trauma and exploitation and the extractive violence meted out by the process of colonialism on the tangata whenua and the landscape of Taranaki's west coast all the way up to the Manukau Heads. As we ascend and travel upwards in the gallery, the works come in and out of view. And in that space, there is an invisible woven thread of time that never leaves us, and we sense it as a vertical up and down movement that takes us to a precipice that makes us feel as if we are going to fall deep inside the earth or ascend into the heavens. Fear, love, hate, beauty and indifference are all driven by that sense of standing at the precipice of spiral-time, and when all these feelings congealed in one moment, we are then struck with astoundment. Well, for this reviewer, that is what moved me with Tai Moana Tai Tangata.

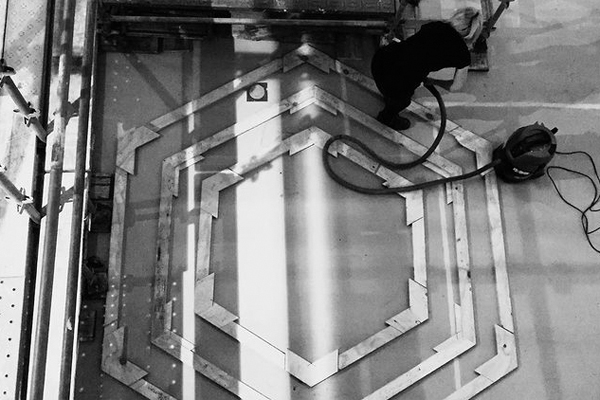

Graham had taken on the research for the project to address the proverb Te Kiwai o te Kete (holding together the handles of a shared basket), an alliance forged between Tainui and Taranaki Māori during the New Zealand Land Wars. He conceived the exhibition as an opportunity for Tainui and Taranaki Māori to restate these principles in the present and in the face of pressing ecological challenges. Coupled with his interest as a child with monuments of colonial conquest of Māori that littered that Waikato landscape, he rejigged the larger-than-life sculptures within the vertical space to be viewed in overlaid vistas that collapses and contrast the works with one another horizontally and vertically. To do this, Graham produced several maquettes of the artworks on a scaled model of the gallery to work out a spiral configuration that makes us ascend the space. At the same time, each sculpture stands out in contrast to one another on different levels of the gallery. The small floor layout and unusual vertical space with small intermediate mezzanine landing spaces of the Govett Brewster lend themselves wonderfully to this notion of the spiral of time or wā in our movement through the gallery.

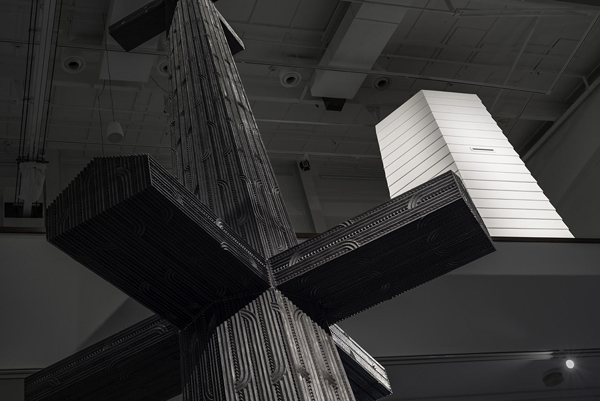

The most striking of the works is graphite covered monolithic towering sculpture titled Cease Tide of Wrong-Doing by the entry, which rises three floors with carved vertical notched tāniko patterns that taper to a needle-like point. The tower was designed to incorporate the ritual form of a niu or divining pole used by the Pai Mārie religion of Taranaki Māori to receive divine signals of coming war or peace. Two sections of the tower have cross-way extrusions in the form of small pātaka food storage to mark the abundance of resources extracted from Māori. As you ascend the gallery to see the other three monumental sculptures, Cease Tide of Wrong-Doing is always visually present to frame the other works, a foreboding and exquisite symbol of gluttony and greed.

The other graphite work, Maungārongo ki te Whenua, Maungārongo ki te Tangata, is the most beautiful piece in the exhibition. Graham's reworking of the above Māori incantation meaning 'peace to the land and people,' forms a pātaka (food store) with wagon wheels that are intricately carved in the manner of the Motunui pātaka panels that are in the Puke Ariki Museum a few streets from the exhibition. In an interview with Graham (personal comments, 25 April 2021) he stated to me that the pātaka is an architectural form that represents collective Māori identities and resources and contains the people's treasures. The British Crown coveted this wealth and seized these resources by various means. Where Māori initially responded to British settlement with curiosity and generosity, Taranaki Māori quickly learned to actively defend their resources, evoking both Tāmatauenga (the god of war) and Rongomātāne (the god of peace). Maungārongo ki te Whenua, Maungārongo ki te Tangata is mobilised as a wagon that commemorates the dual strategies of Tātokowaru, a broker of peace and a leader in war, and the determined pacifism of Parihaka leaders Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi.

Creating a ritualistic and beautiful world out of so much grief makes this exhibition something of a miracle and one that will be hard to be repeated elsewhere. If you were lucky enough to see it at the Govett-Brewster, then you would have witnessed a contemporary artist at the height of his powers.

Essay: The view from the tower : Brett Graham at the Govett-Brewster

Author: Peter Brunt

Year: 2021

Publication: Art New Zealand, no. 178 : 62–47

Tai Moana Tai Tangata, a sculptural installation by Brett Graham, opened at the Govett-Brewster last December and proved to be something of a local art-world event, the 'must see' exhibition of 2020 and 2021. Motivated by social media, word of mouth and early reviews, streams of visitors – curators, gallerists, writers, art lovers of all kinds – made the journey to New Plymouth to see it. Evidently, it touched something. But what exactly? And why? And why at this moment in time? The show opened the same weekend as the Auckland Art Gallery's Toi Tū Toi Ora, a survey show of the contemporary Māori art movement from the 1950 to the present. But in contrast to that mammoth exhibition, which seemed to want to close the book on the fractious 'culture wars' and misunderstandings of the past by virtue of its own triumphant occupation of the entirety of the Auckland Art Gallery, Tai Moana Tai Tangata opened a wound even older and deeper in the national psyche. Or re-opened it. For it has no doubt always been there; obvious and visceral to some; invisible, unconscious, or merely 'in the past' to others.

I did not witness the morning pōwhiri at the Govett-Brewster, but from all accounts it was particularly powerful. In the coming together of delegates from Taranaki Māori and Tainui, it acknowledged the origins of the exhibition in a residency by Brett Graham at the Govett-Brewster in 2019 and in the collaboration between him and Te Ātiawa curator Anna-Marie White. The pōwhiri also reanimated the historical alliance between Tainui and Taranaki Māori in their struggle to resist the determination of the colonial government to assert its sole imperial authority over this country and seize land it coveted as essential to the success of the colonising project, which led, as we (should) all know, to major episodes of the 'New Zealand Wars' in the 1860s and ultimately to dispossession of more than three million acres of Taranaki Māori and Tainui land. This history and its resonance in the present are the subject of the exhibition.

Other artists and exhibitions have taken on this history. Selwyn Muru's one-man show at The Dowse in 1979 comes to mind, as does the epic 2001 Parihaka exhibition at Wellington's City Gallery with more than 80 participating artists and writers, both shows landmarks in their own way. But I am not aware of another exhibition which has managed to take its viewers into the time and space of that history in a manner as emotionally affecting and critically charged as Graham's at the Govett-Brewster. Over his substantial career to date, he has developed a mastery as a maker and scenographer, and an ability to distil history into singular and arresting sculptural structures, supplemented with digital video projections, and to stage those elements in a way that elicits the work of memory in the viewer in their own aesthetic terms.

At the Govett-Brewster the show brilliantly exploited the awkward spaces of its main gallery with its exposed levels, corner alcoves, balconies and imposing central staircase. Moving through these spaces created continually shifting, interpenetrating views of the exhibition as a whole. We see monumental sculptural objects from below and above. At ground level we gaze up the length of an enormous carved pole, 10 metres in height, tapering towards a point at the ceiling. We walk around the faceted sides of an enclosed four-sided tower. We re-see these structures partially through gaps in the walls of the video alcoves, or cut off by the mezzanine balustrade, or glimpsed through the interstices of the wheels and hitching poles of an imposing carved wagon. Audio from the video projections seeps into other spaces. From the mezzanine balcony we look down on what we had previously seen looking up, their perspective lies running in reverse. But it is also apparent, as we learn their titles and absorb the text panels (which do not 'explain' the works so much as provide points of historical and biographical entry), that these structures and cinematic projections are taking us more specifically into memory space.

Furthermore, they cast us as participants in their invitations to anamnesis (active remembering), making us part of the exhibition's performative structure. In ascending the grand staircase towards O'Pioneer, a round 'cake tin' 'fortress' with planar sides carved with Victorian floral emblems and pierced with vertical gun turrets, we are required to walk on another work, Purutapu Pōuriuri (Black Shroud), a quilted black textile carpeting the stairs and decorated with the insignia of British military forces. Indeed, the entire pathway through the exhibition is the implicity extension of that ritual act. 'Walk on me' has been a standing invitation of contemporary Māori artists since Diane Prince first made the call to walk on the New Zealand flag at Korurangi at the Auckland Art Gallery in 1995 – to general public controversy. The re-enactment of that gesture, wittingly or not (since to have seen Graham's show is already to have walked on it), is an invitation, after the fact, to rethink the ethical foundations of our national project, Treaty settlements and official biculturalism notwithstanding.

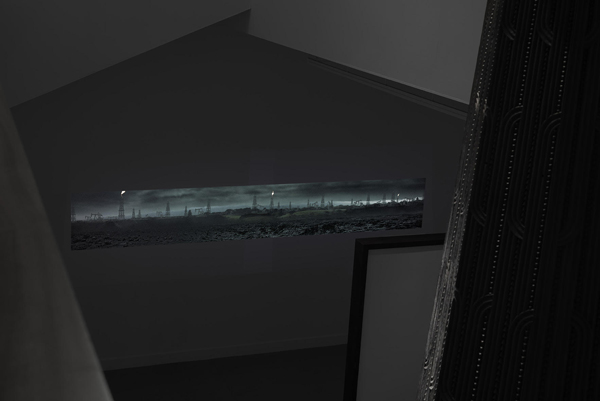

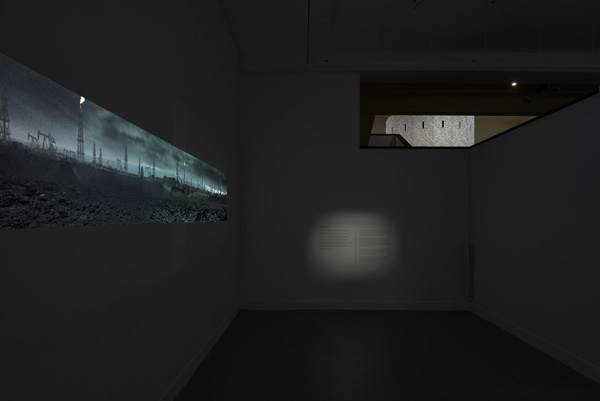

O'Pioneer takes its name from a fortress-like government gunship, used in the campaign against Tainui. Its counterpart in the exhibition is the aforementioned tower, another 'fortress' entitled Grande Folly Egmont, painted another shade of white and also pierced with narrow gun turrets, but its turrets are horizontal. The dimensions of those turrets are scaled up to become the framing rectangles of the animated video projections, which become in effect the tower's 'views'. Watching them, we are placed inside the tower, again becoming participants in the exhibition's narrative and performative constructions. In one projection, entitled Ohawe, we are transported into the past (or the past-present), travelling, dreamlike, along the sheer cliffs of the Taranaki coastline towards the Waingongoro River, beyond which, we are told, lies the territory of 'independent Māoridom'. Other sequences take us north to the Manukau Heads and mouth of the Waikato River, a critical artery in the Waikato Wars down which O'Pioneer churned its way, an impregnable floating 'tank' firing on Māori on either side. In the other protection, called Te Namu, which is the name of the pā where Māori prophet Te Ua Haumēne founded Pai Mārire, we are transported into the present/future to witness the nightmarish vision of a thick, churning black seascape and a coastline of endless working oil rigs periodically blasting flares into the polluted atmosphere. The 'views' from Grande Folly Egmont and O'Pioneer thus evoke a temporal dimension that extends to everything from the beginning of the Taranaki wars when Governor Browne and imperial troops were intent on seizing land at Waitara, to the invasion of the Waikato, to the occupation of Parihaka by government forces in 1881, to the current offshore iron-ore mining projects in south Taranaki, opposed by Taranaki iwi of our own day – all these histories and auguries of the future condensed into the viewers' present, as they are faced with these works there and then in the gallery.

The overall effect of the exhibition, however, is not a demand to relitigate history but rather the imperative at this historical moment in time – mid-global pandemic, imagining a post-pandemic future – to critically confront the values that have dominated and contested our nation- (and world-) making project. That confrontation is materialised in the presence of two works derived from the historical struggle of Taranaki Māori both to preserve the bases of its tribal identities in land and tikanga and to appropriate the prophetic tradition of Judeo-Christianity in the face of the contradictions of the colonising onslaught, manifestly based in avarice, theft, war and the worship of false gods.

One is Graham's reimagining of a Pai Mārire niu pole, a divining structure rising the full height of the gallery, carved with pākati designs, crossed at two points with model pātaka forms, and painted black. Titled Cease Tide of Wrong-Doing, it voices a prophetic, Old Testament-like admonition of a kind not often heard in art gallery spaces, for it echoes tradition both inside and outside the dominant political, social and cultural order.

The second work, entitled Maungārongo ki te Whenua, Maungārongo ki te Tangata, is a large wagon in the form, again, of a pātaka. Exquisitely carved in the traditional Taranaki style and painted a dark metallic black, it commands the centre of the mezzanine floor in view of O'Pioneer on the landing and both Grande Folly Egmont and the niu pole rising from the levels below. In many ways it is the most intense work in the exhibition. On the one hand, its form embodies the principles expressed in its title, the pātaka as a repository of the cultivated wealth of the land for the life and wellbeing of the people, a wealth willingly shared by Taranaki Māori, even with their oppressors. On the other hand, its side poles reach up to dramatic end points carved with contrasting facial expressions, one with the challenge of peace, under the aegis of the god Rongomātane, the other with the challenge of war, under the aegis of the god Tūmutauenga. In their contradiction, they recall the grave decision forced on a people, newly committed to an ethos of peace and peaceful co-existence with the Pākehā, to choose the path of war in order to protect the ideas the pātaka stands for. And in real terms they lost that war at great cost to human life and, as in the Waikato, the loss of most of their tribal land. Whether they lost the war of competing values, however, is an open question that is still being played out in history, now more critically than ever. Graham's decision to employ the Taranaki carving style in creating the work, in effect, reanimates the moral ethos at stake in their common conflict with the colonisers and brings that ethos, again, into the present, into the space and time of the work and viewer in the gallery.

These are extraordinary themes to take on in an exhibition. They cut deeply into the nation's cultural memory. They are at the heart of Tainui and Taranaki Māori's historical alliance. And they are personal to artist and curator. It is sobering to read, having watched the video Ohawe, that 'Graham's great grandfather, Te Ngarue or John Joseph Graham, was buried in an urupā on a cliff near the mouth of the Waingongoro River, which has since collapsed into the ocean', and that Graham visited this site during his residency. It is equally significant to know that Anna-Marie White is from Waitara, over which the Taranaki conflict began. Reading further that 'the black sands of Te Uru [in West Auckland] are mined at the Waikato River mouth and piped to a steel mill near Graham's home in Waiuku' was a realisation of the degree to which personal genealogies have intersected with the past/present histories being summoned up in the exhibition. Those black sands are evoked in the metallic colour of the pātaka wagon, its flickering glints memorials perhaps of Graham's paternal ancestor, who has become part of the ocean. Graham's trajectory to this latest exhibition has been in many ways its own journey to the ocean, and in this show he brings it back to us.

There is a strange philosophical tone running through the exhibition that is encapsulated in its titles. Cease the tide of wrong-doing is like an oxymoron, like commanding the tide to permanently recede. O'Pioneer is like a hymn-become-a-lament for a culture trapped in the fortress of its own making. Grande Folly Egmont juxtaposes the view from the tower with the view from the mountain. Tai Moana Tai Tangata pairs the 'tides' of the ocean with the 'tides' of human actors, invoking their inevitable cycles and repetitions. The latter in particular reminded me of that biblical passage from the Book of Ecclesiastes about times and seasons: 'For everything there is a season and a time for every matter under heaven... a time to plant and a time to pluck up what is planted; a time to kill, and a time to heal...', and so it goes on. But the tone of wistful equanimity in these famous verses masks their author's deep pessimism about the passage of human life, which he sees as an eternal round that does not improve the state of humankind. Rather, each generation repeats the pattern of the former. Wisdom is better than foolishness but even wisdom, in the end, is 'chasing the wind'. The thrust of the book, in fact, is the author's deep pessimism about wisdom. But who is the author? This seems a crucial question in thinking about where Tai Moana Tai Tangata is coming from. One thing that is clear from the biblical text is that the author speaks from a privileged position. He has had all the pleasures the world can offer, he has had many labourers ('slaves') work for him, he has built flourishing gardens and grand architectural structures, he has had great achievements. The wisdom of Ecclesiastes is the wisdom of the ruler. It speaks the fatalism and resignation of the privileged and the powerful, who believe that nothing people do can make a difference in the course of time (or that all human doings are foreordained). And perhaps he is right. But the wisdom of Tai Moana Tai Tangata comes, I think, from a different place and different experience of time. It comes from the struggle of the colonised, which is ongoing. The exhibition would not exist if it was felt it could not make a difference.

Review

Author: Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua

Publication: Artforum

Ka pari te Tai Moana

Ka timu te Tai Tangata

When the Ocean tide rises, the Human tide recedes.

. This whakatauākī, or proverb – first uttered in 1822 by Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha to Te Wherowhero, Waikato leader and first Māori king – acts as an epigraph for Brett Graham's exhibition Tai Moana Tai Tangata, joining intricate relations between Māori, the structures of settler colonialism in Aotearoa New Zealand, and contemporary concerns around economic and ecological exploitation.

The prophetic caution of this epigraph is made evident through the overwhelming presence of Cease Tide of Wrong-Doing, 2021, a ten-meter tall sculpture that dominates both floors of the gallery, and which takes the form of a niu – an erected pole of the Pai Mārire faith used to divine messages of war and peace. Graham's niu is cast in raw black, a towering spike expertly carved with a complex pātaki design and winged with model pātaka (storehouses). If niu were customarily raised in times of intense colonial violence, here the form illuminates how historic wounds seep into the present and against the backdrop of a dystopian Taranaki landscape: the only oil- and gas-producing region within the country.

The richness of the contexts that animate Graham's work is "awoken" by Ngati Koroki Kahukura's recital of Pai Mārire karakia (incantation, blessing), featured both at the show's opening and in its transportive soundscape. These contexts are communicated with spectacular support from exhibition curator and Te Ātiawa scholar Anna-marie White, who recently completed a doctoral thesis on Graham and his place within contemporary Māori art. The artist's oeuvre and his surrounding scholarship prove to be a significant development in the multitudinous field of Indigenous artistic practice, both here and abroad.